Bank crises: what’s going on and what happens next?

Over the past two weeks, the banking sector has been in focus. First, Silvergate failed. Next, Silicon Valley Bank failed, making it the second largest bank failure in US history after Washington Mutual in 2008. Then, Signature Bank failed - the third largest bank failure in the US. Finally, Credit Suisse, a 166 year old Swiss Institution considered to be a systemically important bank, failed. It’s hard not to wonder if they are all interconnected. Each bank had its unique issues, but the common link between them was a lack of confidence in their stability from their depositors. Will more banks fail? Our goal of this week’s blog is to provide you with a deeper understanding of how banks function, discuss why the banking sector has come under pressure, review what happened at Silicon Valley Bank, and give you our thoughts on what could happen next.

A background on banks

We all know what a bank does from a customer perspective, given that we all have bank accounts. You place deposits in a bank, and you rely on the bank to receive your income and pay your expenses. The main parties involved in regulating banks are the Office of the Comptroller (“OCC”), which is part of the US Treasury; the Federal Reserve (“the Fed”), and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp (“FDIC”). Each of these entities has their own responsibilities, but simply put, OCC handles laws and regulations, the Fed is our central bank who determines interest rates, and the FDIC provides protection for up to $250,000 of cash held with any bank.

Banks are complicated entities that make money in a number of different ways, but at the core of all banks is net interest income. When banks receive deposits from their customers, they aim to make money on those deposits in one of two ways: a) lending and b) buying investments. Lending will vary depending on the bank’s customers, but can include anything from mortgages to commercial loans. Investments held by banks are highly regulated, particularly in the largest banks. During the 2008 financial crisis, banks took a tremendous amount of risk with the investments they purchased, and thus the rules of what types of investments banks can hold and the concentration of these higher risk investments became much more strict. While there are distinct differences in the way that small banks versus large banks report to regulators, generally speaking, the balance sheets of banks are in a much stronger position than they were in 2008 as a result of increased capital requirements.

The goal for both lending and investments are that the interest earned is higher than the interest paid to depositors. As a simple example, let’s say you deposit into a bank and the bank is paying you 1% interest. The bank may use your deposits to issue a mortgage to another customer. The customer is paying 6% interest on their mortgage, and so the bank makes 5% on these deposits.

A bank’s balance sheet or net worth statement is essentially the opposite of an individual. The assets are represented by loans outstanding to customers and investments held by the bank; the liabilities are the deposits of customers. Why? Because deposits are owed to customers at any time they need them. Banks usually have no issue with giving their customers the deposits, because with a highly diversified customer base, all customers won’t be drawing upon their deposits at the same time.

Deposits are bank liabilities

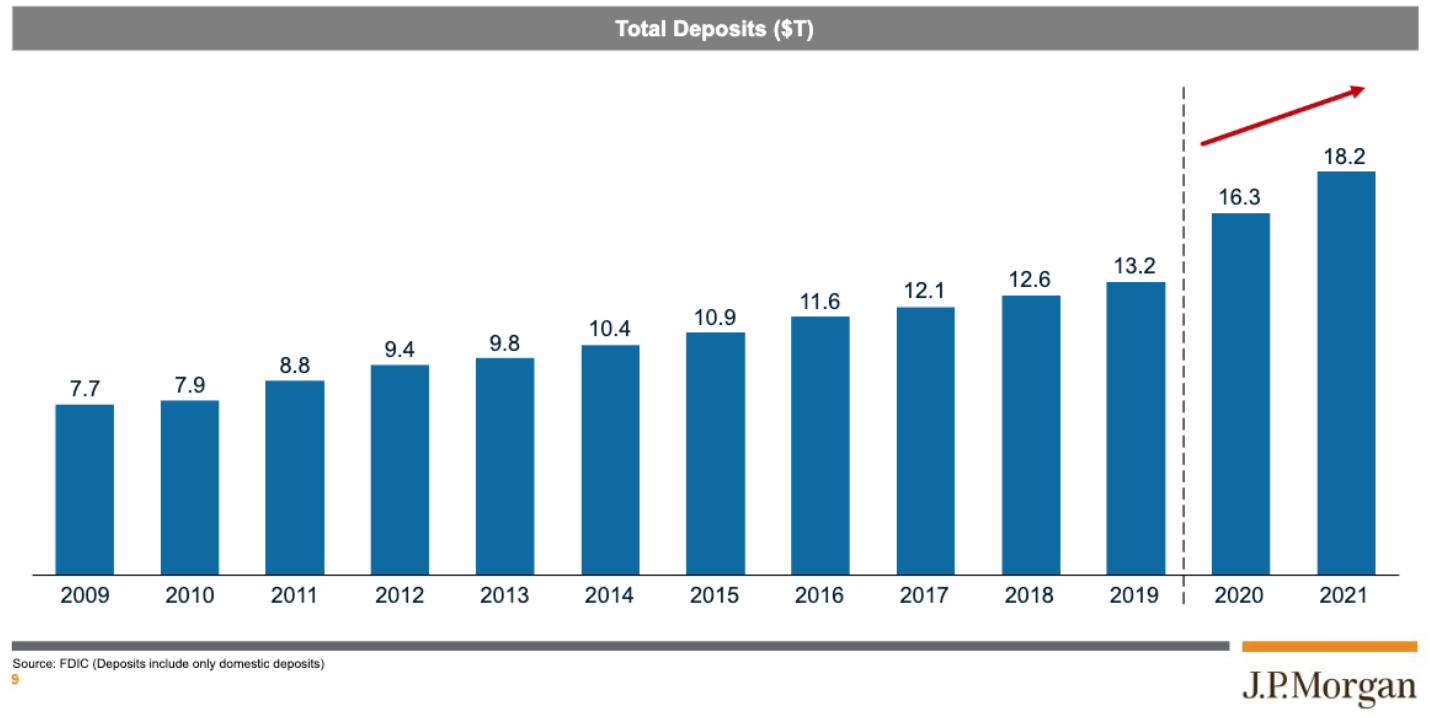

Since 2008, we’ve been in a very low interest rate environment, and the economy has been growing. From 2009 through 2019, the FDIC reported that domestic deposits grew from $7.7 trillion to $13.2 trillion. With the COVID crisis in 2020, the economic stimulus package provided tons of money to both individuals and businesses alike. Over the next two years, deposits grew from $13.2 trillion to $18.2 trillion, essentially squeezing ten years of deposit growth into two. The chart below from JP Morgan shows the COVID surge of deposits into US banks.

Deposits have to go somewhere

One of the reasons banks are attractive to customers is their ability to lend. We have many clients who have received offers from banks such as “put $250k into an account with us and we’ll give you a discount on your mortgage”. Similarly, commercial lending happens the same way. If you’re a small business working with a local bank, it’s likely they will be able to provide you with better lending terms than a larger bank. Oftentimes these banks understand their niche client base better, and can take a more bespoke approach to credit analysis.

Loans have always been a big part of bank income, but since the 2008 financial crisis, loans as a percentage of total assets has dropped significantly. Whereas in the 1990s, loans represented almost 60% of bank assets, today, they represent 40%. Below is a chart from the New York Fed’s Quarterly Trends for Consolidated U.S. Banking Organizations in Q3 2022.

The remaining 60% is split between cash and cash equivalents (about 20%), and investments (about 40%). The investment portfolio of a bank is captured and reported to the regulators as one of three categories:

Trading: Expected to be sold in the near term

Held to Maturity: Debt securities that are intended to be held until they mature.

Available for sale: All other investments (debt & equity) that aren’t captured in #1 or #2.

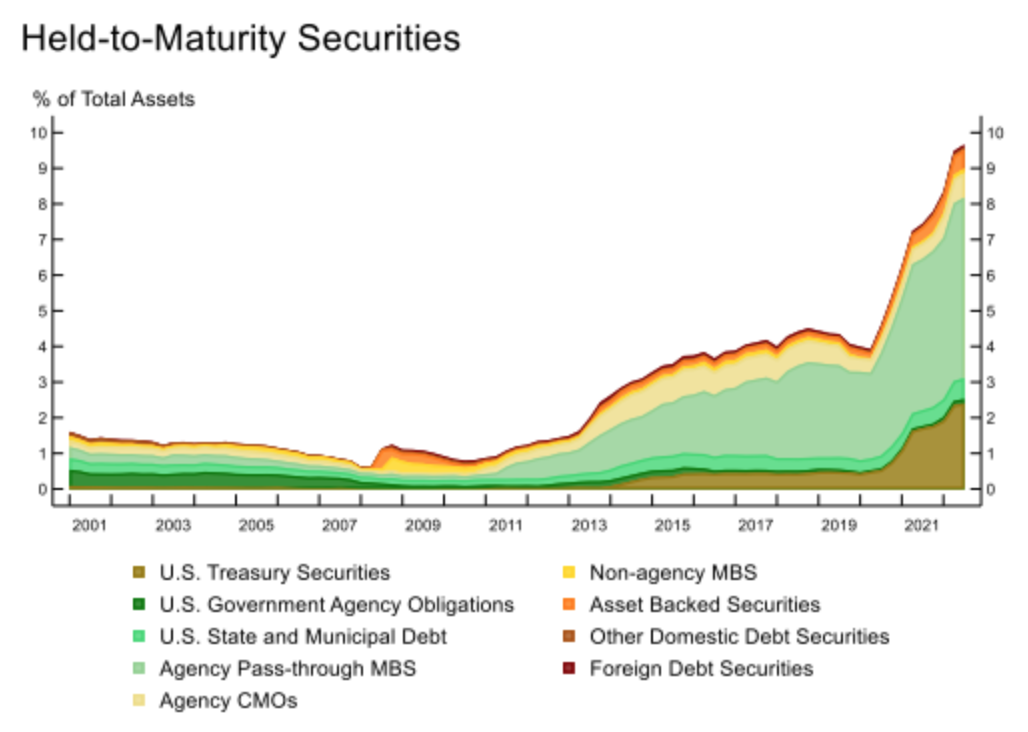

The biggest area of growth was in held-to-maturity securities. The chart below is again from the New York Fed’s Q3 2022 report.

Banks are required to maintain certain capital ratios to ensure they are not taking undue risk, and are required to report these to the regulators. However, smaller banks do have less strict requirements than large banks in terms of what is reported:

Big bank capital ratio includes mark to market on trading securities and available for sale. Held-to-maturity is reported at par value.

Small bank capital ratios include market to market on trading securities only. Held-to-maturity and available for sale are reported at par value.

What this means is that the impact that interest rate fluctuations had on smaller banks was not fully captured by the regulators.

How 2022 teed up the bank failures

In 2022, bank deposits dropped from $18.2 trillion to $17.7 trillion. This meant that depositors were calling upon their cash. A number of factors likely contributed to this decline in deposits, but one of the biggest factors was rising interest rates.

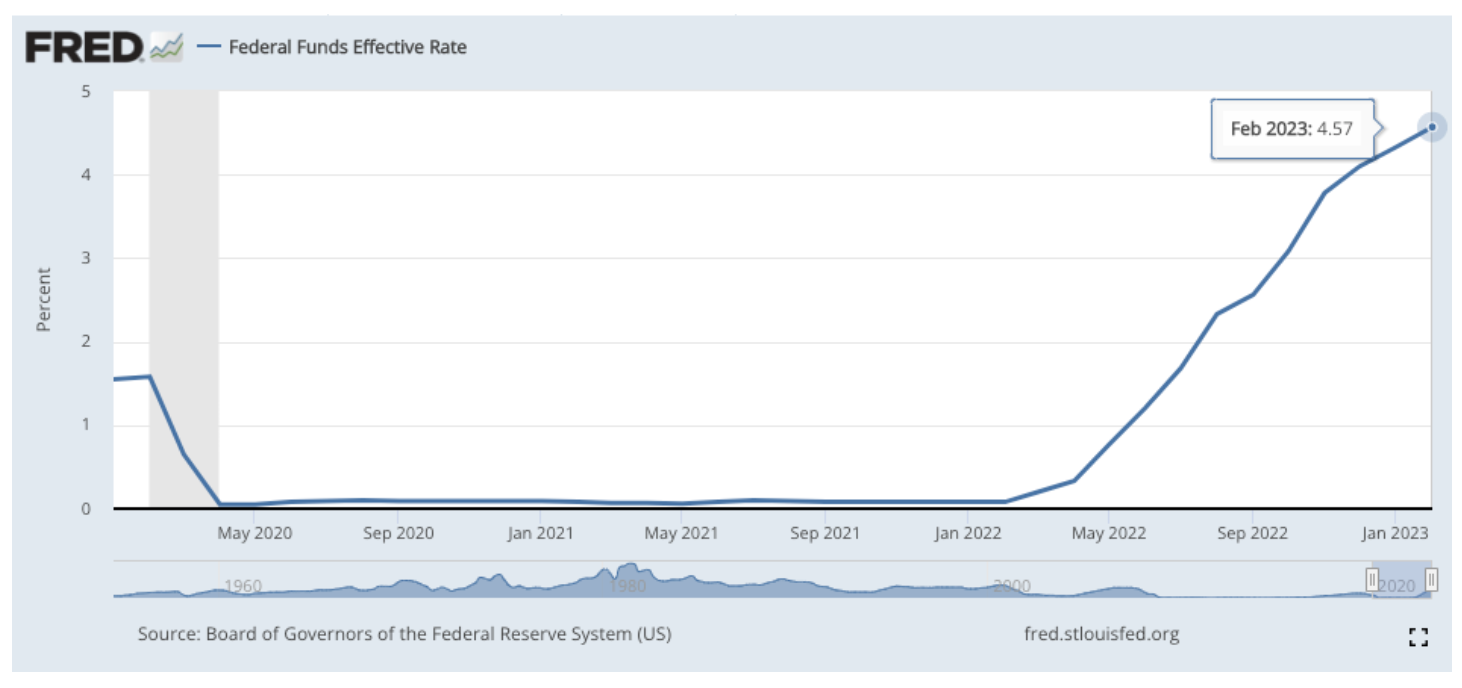

During 2020 and 2021, as an investor (individual or business), your banks weren’t compensating you on deposits, but neither were the safe alternative, treasury bonds. As the Federal Funds Rate rose in 2022 from 0% to 4.1%, investors started to reallocate their capital. Instead of keeping millions of dollars in the bank earning 0.03% (or something miniscule like that), now funds can be invested in short term treasury bonds that are providing a solid yield, and are backed by the full faith and guarantee of the US government.

This alone wasn’t enough to trigger a full blown banking crisis, because banks invest in safe securities, primarily bonds (treasury bonds and agency mortgages). The main issue is that bond prices have an inverse relationship to interest rates. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall.

What happened to Silicon Valley Bank? Can this happen to any bank?

Silicon Valley Bank (“SVB”) was the extreme case of what is described above. SVB had oversight problems within the bank, including a lack of Chief Risk Officer for a period of 8 months! This is essentially unheard of in the banking world.

They were at the top of the charts in terms of growth in deposits for 2020 and 2021. Their customer base was highly concentrated in venture capital funded businesses, many of whom received venture funding and economic stimulus. In 2022, venture funded businesses and technology companies came under pressure, experiencing a sector-level recession, and many companies needed to use cash to survive.

SVB had a huge influx of depositor demands for money, and they had to sell investments to meet them. When they sold bonds to meet demands in the week of their failure, they lost $1.8 billion dollars on the sale, which was more than their entire 2021 net income. This wasn’t necessarily due to investing in risky assets, but rather not taking interest rate risk into account when investing the portfolio. This was a massive and detrimental oversight.

Let’s give an example: SVB buys a 30-year treasury bond yielding 1.25% in May 2020. Their intent is to hold this until maturity. If you decided to buy a 30-year treasury bond in February 2023, this same bond would yield 3.625%. This is a difference of 2.375%, meaning that SVB is now giving up 2.375% each year over the remaining 27 years of the bond. Today, the bond that SVB bought in 2020 is priced at $58. This price discount of $42 to par value (or the amount you get back when the bond matures, $100), is what the market is willing to pay to receive 1.25% interest.

This is exactly what happened.

The four banks which have failed each had a unique risk, which made them more susceptible to a bank run. Silvergate was associated with the FTX / Alameda Research scandal of cryptocurrency. Signature Bank similarly had a concentrated customer base in cryptocurrency. Credit Suisse had many issues prior to SVB. Coming into 2023, the stock price was down 80% from levels 5 years prior due to a number of different scandals.

Digging deeper into the overall banking industry, the Fed created a big problem. Yes, balance sheets are in a strong position, i.e., invested in safer investments if they can be held to maturity. However, the combination of a rapid rise of deposits, and thus investments made by banks at a time when interest rates were nearly 0% has caused a huge duration mismatch at the banks. The banks that took duration risk, i.e., invested in long term bonds, have been most highly impacted. Below is a chart from the FDIC showing the current unrealized losses of bank portfolios at -$620 billion. Reuters reports that some experts think this is understated, and the actual outstanding losses could be as much as -$1.7 trillion.

What happens next?

In our view, the Fed and Treasury needs to restore confidence in the banking system. This can come in two ways: 1) guaranteeing that all depositors will be protected in the case of a bank failure, not giving preference to some banks over others; and 2) easing monetary policy by halting rate increases and/or cutting interest rates.

The first is important, because a bank run at any bank could trigger issues. The Fed has taken some steps to reduce the risk of bank failures through a facility that was established. This facility will protect against the mark-to-market risk of treasuries, agency debt, and mortgage-backed securities. What this means is that instead of realizing a loss on the bond that they had to sell (like the $1.8 billion SVB lost), banks can borrow money from the Fed to pay depositors. While this is a reasonable offer from the Fed, it’s still bad for banks. They avoid the loss, but they still have to pay 5% (the prevailing Fed Funds rate) to hold onto an investment generating 1.25%.

Then, if bank runs are higher than the investment piece of the portfolio, assuming 40-60%, then depositors’ capital could still be at risk. Loans are much more customized, and if they were issued at fixed rate, they may be difficult to sell.

While we think the government will come in to protect depositors, there has been some mixed messaging. Fed Chairman Powell said this week: “All deposits are safe.” But Treasury Secretary Yellen hasn’t clearly stated that FDIC limits will be increased. Although there’s no reason that individuals and businesses should be moving their money, because the Fed shouldn’t be able to treat some banks differently than others (they saved SVB depositors, so they need to save others), there’s no downside to switching to a bigger bank. As such, many people are doing so. While First Republic is a well run bank, the clientele is geographically overlapped to SVB, which may be the reason First Republic could be next in a line of bank failures.

Second is related to interest rates. Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management, wrote that the events in banking correspond to a 1.5% increase in the Fed funds rate. “In other words, over the past week, monetary conditions have tightened to a degree where the risks of a sharper slowdown in the economy have increased,” he said. The language used at the Fed meeting this week is very important as a result. Despite the banking crisis in the making, Chairman Powell delivered the message this week that the Fed increased their target rate by 0.25%. In the short term, we think this messaging was to alleviate the alarm bells. Had they adjusted course, confidence may have quickly declined. However the issue is that by raising rates, this continues to exacerbate the risk at hand: banks have a duration problem.

What can you do

For certain, none of us can individually control the outcome of what happens next. While the banking system is robust, and we do believe the Fed and Treasury will protect depositors, it’s quite possible there are more banks that will fail. The best steps you can do to protect yourself is diversify across financial institutions to minimize your uninsured deposits by keeping no more than $250k per person in a bank account. For most individuals, this is advisable. Given that high yield savings accounts, certificates of deposit, and treasury bonds are all yielding 3-5%, there’s no reason to let cash sit idle.

For businesses, this becomes a greater challenge. Moving banks isn’t as easy, and oftentimes $250k is not enough in an account to maintain ongoing business operations. We do believe the US government will protect uninsured deposits, but during this time, remain in close contact with your bank to understand your options. Sometimes banks offer sweep programs, where they work with other banks to provide you with higher degrees of FDIC insurance. Additionally, they will be on the front lines of understanding how the Fed and US Treasury is able to help in the case of instability.

No matter what your situation, if you have any concerns, this is a time to be reaching out to financial professionals who support you. Talk to your banker and your financial advisor, and make a plan that provides you with the peace of mind you need to live most comfortably.

Follow our Instagram for personal finance tips and inspiration.

Stephanie Bucko and Cristina Livadary are fee-only financial planners based in Los Angeles, California. Stephanie is the Chief Investment Officer and Cristina is the Chief Executive Officer at Mana Financial Life Design (FLD). Mana FLD provides comprehensive financial planning and investment management services to help clients grow and protect their wealth throughout life’s journey. Mana FLD specializes in advising ambitious professionals who seek financial knowledge and want to implement creative budgeting, savings, proactive planning and powerful investment strategies. As fee-only fiduciaries and independent financial advisors, Stephanie and Cristina never receive commission of any kind. Stephanie and Cristina are legally bound by their certifications to provide unbiased and trustworthy financial advice.