The Math of Inheritance

Have you ever wondered about the math behind a financial inheritance? Inheriting money or assets can be a significant life event, and it's important to understand the implications.

First, keep in mind that separate types of tax may apply to an inheritance. Large estates may be subject to federal estate tax (more about that later). More commonly, for beneficiaries, there may be federal and state income tax, capital gains tax, or state property tax implications associated with inherited money or assets.

What type of tax may potentially be associated with your inheritance largely depends on asset location. Location in this context means what type of holding or account is inherited.

Note: Before we elaborate below, we want to emphasize that if you are coming into an inheritance, it's crucial to consult with a tax professional or estate planning attorney who can review the specific details of any accounts and trusts, and provide guidance on the tax implications of inheriting assets. Taxation can be complex, and professional advice can help ensure that you understand and fulfill your tax obligations correctly.

The rest of this blog will cover key items and elements of inheritance, to prepare you and help you understand the math associated with taxation and more. We hope this information can inform your roadmap for planning.

Retirement Assets

When inheriting a retirement account, such as a Traditional IRA or 401(k), the math of the inheritance can be complex. The SECURE Act made significant changes to the rules surrounding tax implications of retirement accounts; the following observations apply to deaths that occur in 2020 or later. Importantly, taking ownership of a retirement account by transferring it into your own designated Inherited IRA is not a taxable event. The taxable event happens when funds are distributed out of the account. A few (of many) distinctions that will determine the rules directing when and how much in distributions must be taken include:

Relationship of the beneficiary to the account holder

Whether the original account holder had begun taking Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs)

Generally, a spouse may treat the inherited account as their own and take distributions according to their life expectancy. The amount of the RMD is calculated based on life expectancy and the balance of the account. Distributions are taxed as ordinary income.

A beneficiary who is not a spouse, however, will generally be subject to the 10-year rule, which the IRS explains as

A beneficiary subject to the 10-year rule must empty the entire account by the end of the 10th year following the year of the account owner's (or eligible designated beneficiary's) death

Again, distributions are taxed as ordinary income. There is no minimum amount that must be distributed per year, so there is some flexibility for the inheritor to choose the timing of the distributions, and thus, the tax event.

As an illustration, for a beneficiary that takes a $10,000 distribution and has marginal tax rates of 32% (federal) and 9.3% (state) the math might look like this:

For an inherited Roth IRA or 401(k), a non-spouse beneficiary will generally be subject to the 10-year rule but, because of the Roth nature of the account, will not be subject to ordinary income tax on the distributions. Again, a complex set of rules apply so careful planning is a must.

Overall, the tax implications of inheriting a retirement account can be substantial and involve careful math calculations to ensure you are making the most of the assets left to you. It's crucial to consult with a financial advisor or tax professional to navigate the complexities of inherited retirement accounts and make informed decisions that align with your financial goals.

Family Home

In our last post, we promised to break down the math of inheriting a house. Americans are holding on to their homes twice as long as they did 20 years ago. This is especially true for baby boomers: nearly 40% of those born between 1946 and 1964 have lived in their homes for at least 20 years. If you’re inheriting one of these houses, you’ll have several considerations to make.

If you’ll be inheriting a home in California, it’s particularly important to review your understanding of what happens because Proposition 19 in California has made the math on inheriting your parents’ home a bit less straightforward.

To illustrate this point, here’s an example:

June and Jenny are sisters who were born and raised in the SF Bay Area. Their mom, Tammy, bought their family home in the 1980s for $150,000, she’s lived there ever since. The house is now worth $1.5 million. Over the years she lived in the home, she made $300,000 in home improvements.

In this example, Tammy’s cost basis in her home is $450,000 - the price she paid ($150,000) plus her home improvements ($300,000). If Tammy were to sell her house for $1.5 million during her lifetime, she’d have a capital gain of $1,050,000. Per IRS Rules, Tammy could exclude $250,000 of those capital gains because she was selling her primary residence, so she’d owe taxes on $800,000 of capital gains.

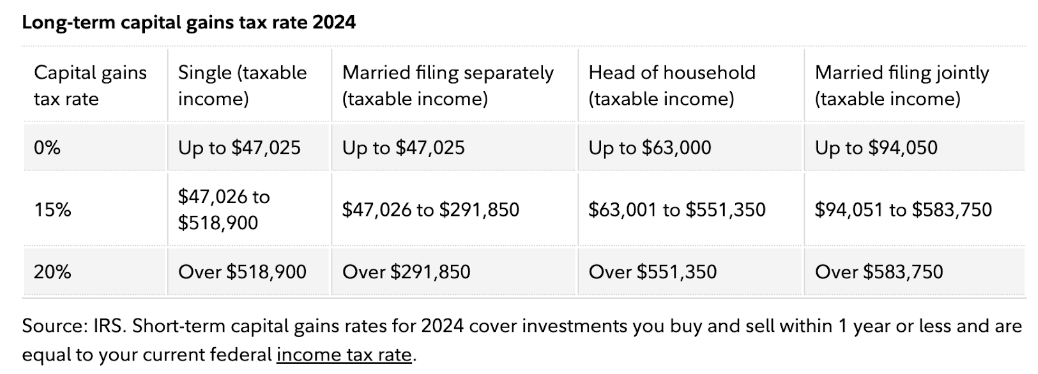

Depending on Tammy’s income in the year of the sale, she could owe up to 38.2% (20% federal capital gains + 3.8% for net investment income Tax + 14.4% for California capital gains taxes) - or $401,100 in taxes! Let’s say that now, instead of Tammy selling the house in her lifetime, she instead passes away, leaving the house to June and Jenny to own 50/50. If the fair market value of the house is $1.5 million when Tammy dies, June and Jenny inherit a house with a cost basis of $1.5 million. June and Jenny both decide that they want to sell the house shortly after their mom’s passing and they end up selling the house for $1.6 million. They will only owe $38,200 of tax on $100,000 of capital gains - the difference between the sale price of $1.6 million and their cost basis of $1.5 million.

Inheriting property is quite tax efficient, but if you live in California there is a new catch. California’s recently passed Proposition 19 enacted a big change for future inheritors. Under Proposition 19 - passed in 2021 - the parents’ property tax basis does not pass onto the child unless the child makes it their principal residence within one year of the parent’s passing. If you plan on keeping the house in the family, it makes a lot of financial sense for one child to agree to make the home their primary residence. Using our example: If Jenny were to decide to move in and make it her primary residence, she’d keep paying property taxes at Tammy’s rate based on a $150,000 house. This would also mean, however, that Jenny would need to have enough additional cash on hand to pay June out her 50% of the house.

If June and Jenny were to keep the house split 50/50 and, instead of either moving in, decide to keep it as a rental property, Prop 19 would bring June and Jenny’s property tax rate based on a $1.5 million house. The annual approximate property tax on a $150,000 house: $2,250. The annual approximate property tax on a $1.5 million house: $22,500.

Taxable Accounts

One of the most common types of inherited accounts is a taxable brokerage account. Taxable brokerage accounts contain investments like stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

When you inherit a taxable brokerage account, the cost basis of the securities in the account is typically "stepped-up" to their fair market value at the time of the original owner's death. This means that for tax purposes, the cost basis of the inherited securities is adjusted to their value at the time of inheritance, rather than the original purchase price.

For example, if the original owner purchased a stock for $50 per share, but at the time of their death, the stock was valued at $100 per share, your cost basis for tax purposes would be $100 per share. This "stepped-up" basis can have significant tax advantages, particularly if the securities have appreciated in value since they were purchased by the original owner.

Oftentimes taxable brokerage accounts are held in a revocable living trust. A revocable living trust is a legal arrangement where an individual (the grantor) places their assets into a trust during their lifetime and retains control over those assets as the trustee. The grantor typically designates themselves as the initial trustee and beneficiary of the trust. They can also name successor trustees and beneficiaries to manage and benefit from the trust assets after their death. Revocable living trusts are commonly used in estate planning for various purposes, including avoiding probate, maintaining privacy, and providing for the management of assets in the event of the grantor's incapacity.

If the taxable brokerage account is held within a revocable living trust and you inherit it, the treatment of the cost basis depends on the type of trust and how it is structured.

Grantor Trust: If the revocable living trust is considered a grantor trust for tax purposes, then the assets held within the trust are treated as if they were owned by the grantor (the person who established the trust) for tax purposes. In this case, when the grantor passes away and you inherit the assets held within the trust, you would typically receive a stepped-up basis for tax purposes, just as if you had inherited the assets outside of the trust directly from the grantor.

Non-Grantor Trust: If the revocable living trust is treated as a non-grantor trust for tax purposes, the taxation can be more complex. In this scenario, the cost basis of the assets held within the trust may not necessarily be stepped up upon the grantor's death. Instead, the tax implications would depend on various factors, including the trust's terms, how distributions are made, and the applicable tax laws.

In either case, we always recommend consulting with a tax professional or estate attorney to review the specific details and provide you with advice.

Estate Tax

In the United States, there is a federal estate tax that applies to large inheritances. Under current law, every individual has an estate and gift tax exemption of $13.61 million. This is a lifetime exemption that works hand-in-hand with the annual gift limit and can be thought of as a bucket. Estate or gift tax is paid on dollar amounts that overflow the bucket.

Throughout your life, gifts over the annual limit to an individual are added to the bucket. The 2024 annual gift limit is $18,000 per individual recipient; any amount over $18k is applied against the lifetime exemption

Upon death, the estate value is added to the exemption bucket.

The top federal estate tax rate is 40%

If federal estate or gift tax is due, it is paid by the estate before funds are distributed to beneficiaries

Some states also have inheritance taxes; limits and tax rates vary widely. It's crucial to understand the federal and local tax laws to avoid any surprises.

Inheriting money can be a blessing, but it's essential to approach it with a clear understanding of the math involved. Take the time to plan and make informed decisions to ensure the inheritance benefits you and your loved ones for years to come.

Follow our Instagram for personal finance tips and inspiration.

Stephanie Bucko and Cristina Livadary are fee-only financial planners based in Los Angeles, California. Stephanie is the Chief Investment Officer and Cristina is the Chief Executive Officer at Mana Financial Life Design (FLD). Mana FLD provides comprehensive financial planning and investment management services to help clients grow and protect their wealth throughout life’s journey. Mana FLD specializes in advising ambitious professionals who seek financial knowledge and want to implement creative budgeting, savings, proactive planning and powerful investment strategies. As fee-only fiduciaries and independent financial advisors, Stephanie and Cristina never receive commission of any kind. Stephanie and Cristina are legally bound by their certifications to provide unbiased and trustworthy financial advice.